Spring is a time of renewal, fresh starts, and plants coming into bloom. Spring is a welcome sight, but considerably less welcome are the allergic reactions that arise from exposure to pollen grains. Pollen, which carries reproductive material for seed-bearing plants, contains proteins and enzymes that the human body often mistakes for pathogens. This overreaction causes allergic rhinitis, better known as hay fever, which can make springtime a struggle for many people. While different plants pollinate at different times of the year, most grasses and trees pollinate in spring. In this guide, we’ll take a closer look at some of the most common types of spring pollen allergies and how you can identify them.

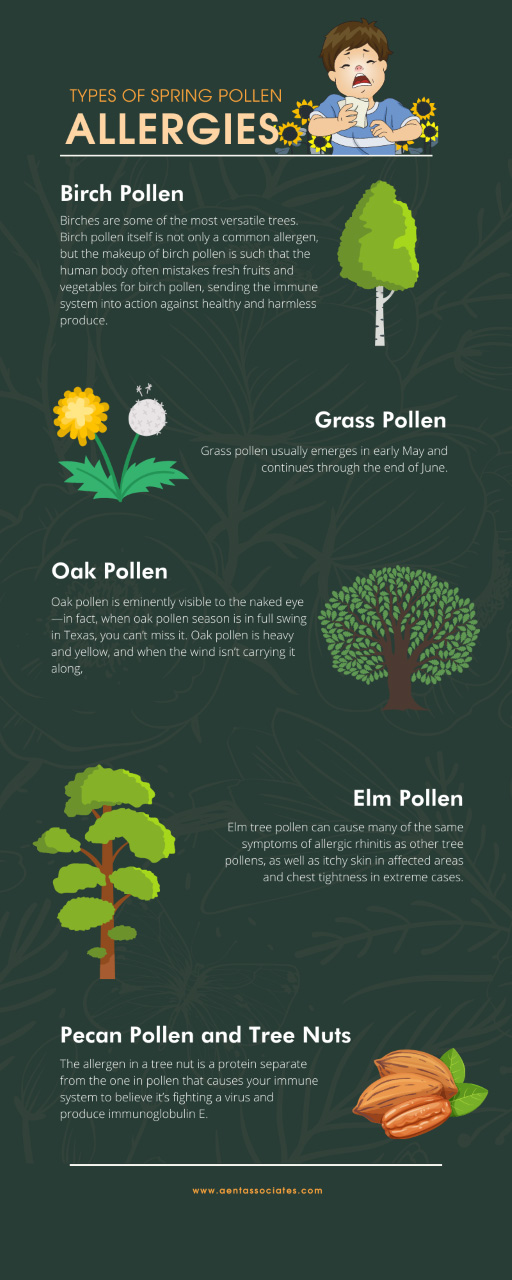

Birch Pollen

Birch trees stand out among fellow trees for their trademark papery bark. If you were so inclined, you could tear off a scrap of white birch bark and take some notes. Birch trees are most common in the cooler climates of North America, particularly around the Great Lakes, Canada, and the northern end of the Appalachian Mountains. Growers have attempted to introduce them south of their natural range as well with mixed results—birch trees generally prefer cooler soil and low humidity. With hard but light wood and a host of useful derivatives, birches are some of the most versatile trees.

Unfortunately for allergy sufferers, this versatility extends to the pervasive allergic reactions associated with its pollen. Birch pollen itself is not only a common allergen, but the makeup of birch pollen is such that the human body often mistakes fresh fruits and vegetables for birch pollen, sending the immune system into action against healthy and harmless produce. This condition, known as oral allergy syndrome, can arise later in life and is a leading cause of adult-onset food allergies. As much as 75 percent of people with a birch pollen allergy can develop allergic rhinitis as a result of eating pitted fruits such as apples, pears, peaches, and apricots, as well as legumes like soybeans and peanuts.

Grass Pollen

When we think of the plants that propagate pollen, the grass beneath our feet scarcely comes to mind. Rather, we associate pollen with flowers and trees, not to mention the bothersome weeds that trigger our allergies despite not being welcome in our yards. Nevertheless, even such domesticated species as Kentucky bluegrass and bermudagrass attempt to spread far and wide with light, dry, and tiny pollen that’s too small to see but large enough to put your immune system on high alert.

Grass pollen usually emerges in early May and continues through the end of June. However, in some parts of the country, grass may get a head start and begin pollinating as early as mid-April. Here in hot and humid east Texas, grass pollen season starts early and ends late, with activity beginning in early March, peaking in June and July, and tapering off during October, making this a spring, summer, and fall allergy—one you’ll have to treat if you want to coexist with the outside world.

Oak Pollen

It’s difficult to deal with microscopic grass pollen that travels for miles. Challenging in its own way is oak pollen, which is among the heavier varieties. Unlike its grass counterpart, oak pollen is eminently visible to the naked eye—in fact, when oak pollen season is in full swing in Texas, you can’t miss it. Oak pollen is heavy and yellow, and when the wind isn’t carrying it along, it’s settling on windshields, patio furniture, and just about every surface you can name, coating them all in its signature yellow dust. Oak pollen is at its worst in April and May, during which time you may develop allergic reactions from the high levels of allergens in the air. After pollen season ends for oak trees, the trouble lingers a little longer—oaks shed their catkins, the flowers that spread pollen, which go brown, dry out, and fall to the ground.

Elm Pollen

Just as Houstonians do, elm trees thrive in humidity. Elms grow throughout the temperate areas of North America, including throughout much of eastern Texas, typically along bayous and rivers where soil is moist. Though most elm trees in Texas pollinate early (typically from late February to early March), some elms may be late bloomers, and elms in more northern climates typically do not begin to pollinate until April. Elm tree pollen can cause many of the same symptoms of allergic rhinitis as other tree pollens, as well as itchy skin in affected areas and chest tightness in extreme cases.

Pecan Pollen and Tree Nuts

The pecan hickory, although native to northern Mexico, has spread north as far as warm temperatures will allow. Pecan trees grow from east Texas and Oklahoma to Georgia, with progress along the Mississippi River as far north as St. Louis and downstate Illinois. Though pecan nuts are what first come to mind as an allergen, the pecan hickory’s pollen, which spreads in the springtime, is a leading cause of allergic rhinitis in people with environmental allergies. While both pecan pollen and pecan nuts can cause allergic reactions, it’s important to note that these allergies have separate origins.

The allergen in a tree nut is a protein separate from the one in pollen that causes your immune system to believe it’s fighting a virus and produce immunoglobulin E. Being allergic to the pollen of a nut-bearing tree does not necessarily mean you will be allergic to the tree nuts themselves, and vice versa. However, it is possible to have concurrent allergies to tree nuts as well as tree pollen. To determine whether one or both aspects of nut trees may trigger your allergies, explore allergy treatment near you. In Houston, Texas, where pecans are prevalent, Allergy & ENT Associates offers testing that will help you clarify which tree nuts, if any, are safe to eat.

Treating Your Pollen Allergies

The different types of spring pollen allergies all cause your body to release immunoglobulin E, which, in turn, encourages the production of histamine. This is the chemical that causes so much of the discomfort we associate with allergic reactions. In mild cases, a simple over-the-counter antihistamine may be all you need to keep allergy symptoms at bay, but more serious instances may call for more advanced tactics. If you feel you may need stronger medications or an immunotherapy strategy in order to deal with springtime pollen allergies, see your nearest allergist.